The Enduring Mystery of “Moldy Mary”

Mary Hunt, believed to be on the left, with a fellow worker inside Peoria’s USDA Northern Regional Research Laboratory, ca. 1943. They are examining agar plates of bacteria exposed to penicillin as part of a worldwide survey effort to find Penicillium mold strains that produced the highest amounts of the antibiotic. (Photo by USDA, D4750-1)

Penicillium rubens strain NRRL 1951 is best known as the bluish-green mold that helped scientists develop methods to mass-produce the powerful antibiotic penicillin during the closing years of World War II.

In addition to saving thousands of Allied soldiers’ lives, penicillin’s mass-production ushered in a new era of antibiotics use to fight infection and disease beyond the frontlines of war that continues even today.

On August 17, 2021, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed a bill designating strain NRRL 1951 as the official State Microbe of Illinois for its medical importance to humanity. The mold strain also catalyzed the wartime efforts of a large team of scientists at the then-named USDA Northern Regional Research Laboratory, now known as the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research (NCAUR), located in Peoria, IL.

Starting in the early 1940s, the team conducted studies that ultimately gave rise to industrial methods for mass-producing the mold and harvesting its precious antibiotic, using a procedure called submerged deep-tank fermentation and a nourishing “brew” of corn-steep liquor and other ingredients. Andrew Moyer, Dorothy Fennell (Alexander), Kenneth Raper, and Robert Coghill were among those who achieved the monumental and well-documented feat (See “For further reading”).

Success didn’t come right away, however.

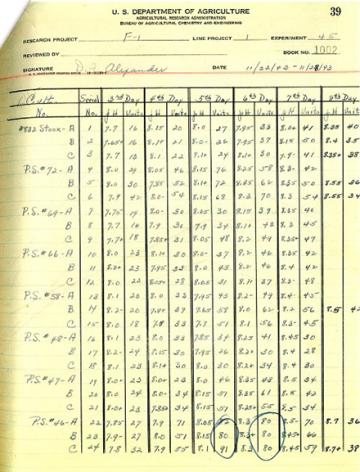

A notebook page signed by Dorothy Fennell Alexander, an NRRL “penicillin survey” team member who worked to identify Penicillium mold strains that produced high amounts of penicillin under submerged culture conditions used by pharmaceutical companies. The circled strain, PS46 (later known as NRRL 1951), was the top performer and became the “parent” of all strains used commercially. (Photo by USDA, D4749-1)

Specimens derived from the original Penicillium notatum mold discovered in 1928 by Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming―and brought to Peoria by two University of Oxford scientists in 1941―didn’t respond well enough to the improved growing conditions the team had created. Additionally, its penicillin yields under the submerged culture conditions required for industrial scale-up by pharmaceutical companies fell short of practical wartime production needs.

A hardier, higher-yielding penicillin strain was needed.

So, Raper, head of the NRRL’s Culture Collection, asked the Army Transportation Corps for help. That service, in turn, collected several thousand new mold specimens from flight destinations to non-combat regions of the world and sent them to the scientists for testing. Specimens also arrived from other U.S. researchers and contributors.

Ironically, the mold strain that stood out among them all—later known as NRRL 1951—came not from the soils of a distant locale, but rather atop a cantaloupe found at a Peoria market.

Who actually found the cantaloupe—and was nicknamed “Moldy Mary” by some—is uncertain.

Arguably, the best-known account centers around Mary Kay Hunt (later Stevens), who, according to news interviews, studied bacteriology and public health while in college. As an NRRL laboratory technician in 1943, she played a visible role in helping collect new mold specimens from produce markets and other local sources and isolating the specimens for research. Indeed, in a 1944 published scientific paper, Raper, Fennell, and Coghill acknowledged Hunt for her contributions.

Hunt herself, in a June 4, 1962 article, offered specific details about her efforts, including cutting up the cantaloupe she found and offering it to coworkers after removing the moldy part. In that same article, though, Hunt referenced the wrong strain number for the mold. Raper, in an October 1, 1976 news article, gave a different account. Instead, he credited a Peoria woman, who handed the cantaloupe to a guard at the NRRL and then left without identifying herself. Raper also alluded to this in an August 1945 research publication.

More recently, a review of penicillin-related research documents archived at NCAUR turned up an interesting find—namely, a copy of an Abbott Laboratories magazine advertisement that was illustrated with a reproduction of a 1948 painting by Douglas Gorsline. The painting depicts a yellow-dressed woman standing at a marketplace entrance, cantaloupe in hand. At the copied ad’s top, someone had written The Original ‘Moldy Mary’ (Mary Lou Finley Roberson), suggesting she, not Mary Hunt, found the cantaloupe. As yet, there’s no conclusive information on who the writer was or how the person knew of Mary Lou Finley Roberson (possibly Robeson).

It’s also worth noting that a number of female NRRL technicians, along with the scientists themselves, searched for local Penicillium specimens on food, produce and like. Additionally, the names of who discovered which moldy items weren’t always recorded in notebooks that were kept. (At the time, a chief focus may have been documenting the source of the mold specimen, its penicillin yield, and growth characteristics.)

Accounts of the cantaloupe’s discovery amid an intensive, global search for a superior Penicillium strain appear in journal articles, academic papers, family lore, feature articles, and other writings past and present. And this speaks to the endearing nature of the basic storyline.

Ultimately, the story of penicillin is a coming together of people from all walks of life during a critical time of need―from ordinary citizens and laboratory technicians like Mary Hunt, to the researchers and industry partners who turned Fleming’s 1928 discovery into a life-saving reality.

That communal effort is perhaps the most important message to remember, then and now.— By Jan Suszkiw, ARS Office of Communications.

For further reading:

-

“Discovery and Development of Penicillin,” American Chemical Society

-

“Penicillin: Opening the Era of Antibiotics,” USDA-ARS National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research

-

“Classic Spotlight: Crowd Sourcing Provided Penicillium Strains for the War Effort,” Editorial, Journal of Bacteriology

-

“Natural Variation and Penicillin Production in Penicillium Notatum and Allied Species,” Annual Meeting of the Society of American Bacteriologists, May 3-5, 1944

-

“Penicillin: V. Mycological Aspects of Penicillin Production,” Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society, 61, August 1945

-

“The Mould in Dr Florey's Coat: The Story of the Penicillin,” Eric Lax

-

“Penicillin: Meeting the Challenge,” Gladys Hobby

-

“Moldy Mary... Or a Simple Messenger Girl?” Chris Farris, Peoria Public Library, Peoria Magazine, December 2019

-

“Epic Penicillin Work Here To Be On Air Today,” Dick Hayford Peoria Star, June 17, 1944

-

“If You Get Penicillin, Thank ‘Moldy Mary’,” Chicago Daily News, March 7, 1955

-

“Moldy Mary Gave Penicillin A Boost: Joined Forgotten,” C. Verne Bloch, Peoria Journal Star, May 8, 1962

-

“Out of the Past Comes Forgotten Moldy Mary,” author unknown, Peoria Journal Star, June 4, 1962

-

“Sorry Mary, You’re No Hero After All,” Ronald Kotulak, Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1976

-

Kenneth B. Raper Symposium - Kenneth Raper – Master of Molds