How to Save the Florida Citrus Industry?

Trees infected with citrus greening. (Photo by Marco Pitino).

Imagine a devastating plant disease that sweeps the land, decimating crops. For Florida’s citrus growers, that apocalyptic vision is not a horror movie, but a reality: since it was first identified in the Sunshine State in 2005, citrus greening disease has reduced Florida’s citrus production by a whopping 70%. Without any treatment or cure available, desperate growers have cut down infected trees or abandoned their groves entirely. Scientists have been racing to come up with a solution. Now, one enterprising team believes it may have one, in the form of: stingrays.

Like other organisms, stingrays have an immune system. Unlike most organisms, however, the rays’ system produces an antibody with a functional domain that is both far smaller and more stable than most. These special antibodies, or nanobodies – termed “mantabodies” by the research team – are specialized proteins that can help other organisms fight off infection. Essentially, the researchers plan to treat the rays as a sort of all-purpose pharmacy, where they can introduce a novel pathogen like the citrus greening bacteria, and the rays will generate an immune response specific to that pathogen. The genetic material (gene) encoding this specifically-targeted antibody can then be placed in modified plant cells that grow as a symbiont – an organism that lives in a close, mutually beneficial relationship with the diseased organism.

Alternatively, researchers can culture the modified plant cells in large vessels and then harvest the antibodies that the cells produce for inoculation into citrus trees. The resulting antibody therapy would prevent or cure disease development in the trees. The approach could, in theory, be applied to other organisms too, and the researchers plan to use the technology to target pathogens that invade farmed fish, honey bees, and more.

This project was a 2022 winner of ARSX, an annual competition that asks ARS scientists to propose innovative, high-risk, high-reward ideas that cross disciplines and break boundaries to solve our most pressing challenges.

.

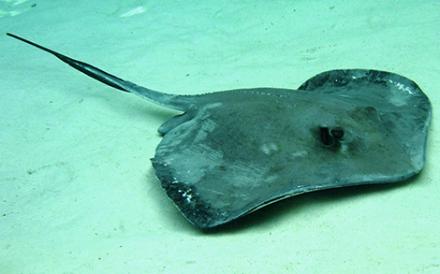

A southern stingray, Hypnum americanus, swims along the seabed. (Photo courtesy of Matt Ajemian, Ph.D., director of the Fisheries Ecology and Conservation Lab at FAU-HBOI)

The project team includes researchers from ARS, the Florida Atlantic University Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, in Fort Pierce, FL, and the and U.S. Department of Energy Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education in Oak Ridge, TN. Team member and ARS research molecular biologist Michelle Heck is using USDA’s SCINet high performance computing clusters to analyze the stingray genomes, and she is applying a powerful artificial intelligence (AI) approach called AlphaFold to identify the mantabody genes.

“Using AlphaFold, which was just released two years ago, we can rapidly and accurately predict the shape of all the stingray proteins,” explained Heck, who works at ARS’s Robert W. Holley Center in Ithaca, NY, “And we can find the ones that look most like what we think a mantabody protein should look like.”

The researchers are also taking advantage of other advances in biotechnology, like the mRNA technique that was used to deliver Covid-19 vaccines. They believe that their project could, in turn, advance biotechnology even farther.

“You can modify almost anything with an antibody treatment,” said Joseph Krystel, a team member and research biologist at the ARS U.S. Horticultural Research Lab (USHRL) in Fort Pierce, FL. “You could stimulate the immune system of a citrus tree, or you could suppress a particular set of genes if you wanted to. The reason we don’t do it now is that it’s cost-prohibitive. But the mantabody platform could give us a more cost-effective way to do it.”

It could also provide farmers with more sustainable biological alternatives to many current practices. Robert Shatters, a team member and research molecular biologist at the USHRL, explained that, “Mantabodies could be applied to veterinary aspects of agriculture, and a number of plant pathogen issues. We think this project would have a really broad impact, and that’s why we’re excited about it.”– Kathryn Markham, ARS Office of Communications

You May Also Like: