Hunting a Tree Killer

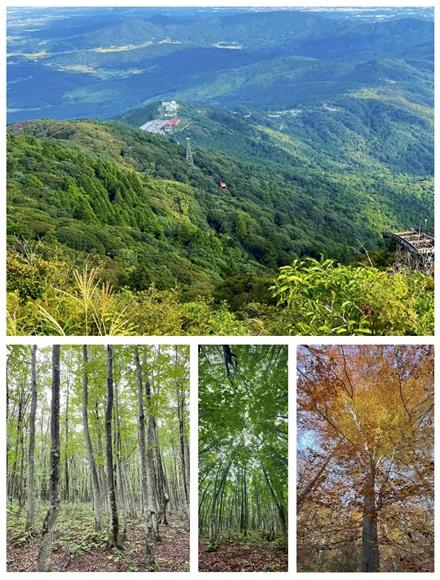

If you live in the eastern United States, it’s likely that you’ve experienced the subtle natural beauty of the American Beech. But the beech also provides much more: a wealth of benefits to the ecosystem, supporting all manner of animal and plant life. Now, however, it is under attack. Scientists first recognized Beech Leaf Disease (BLD) in 2012, making it a relatively new ailment. Scientists believe the culprit may be an invasive nematode – a worm-like creature – most likely from somewhere in Asia, much of which has similar climates to areas of the U.S.

In the years since it arrived, the disease has wreaked havoc on the tree, in part because of the nematode’s extraordinarily prolific breeding.

“If you live near a beech diseased forest, it’s unbelievable,” said Paulo Vieira, a molecular biologist at the Mycology and Nematology Genetic Diversity and Biology Laboratory in Beltsville, MD. “Every year I go to collect samples, the deforestation is so high that you know something is wrong, the forest doesn’t look healthy.”

“The number of nematodes that you find in these buds and these leaves is astronomical,” he added. “I’ve never seen anything like it in my life.”

Vieira is leading a research project that is tackling the disease, with three main goals: First, they want to provide faster mechanisms to diagnose the disease.

Second, they want to understand the mechanism by which the nematodes may be causing BLD. “Nematodes secrete proteins,” Vieira explained, “and those proteins regulate the mechanism of the plant, so there’s a molecular dialogue between the nematode and the plant when they interact with any tissue of the plant.”

The disease process is complex, because the attack begins long before a leaf can even unfurl; the nematodes feed on the bud tissues (i.e., bud scales and leaves) early in their development, causing a tumor-like disease. If they are present in large numbers (i.e., thousands), nematodes destroy the leaf tissue, so that the new leaves cannot break through in the spring. The diseased trees defoliate, making them less able to complete physiological functions like photosynthesis that they need to survive.

Third, and perhaps most important, the researchers are seeking mechanisms that the tree can use to resist disease. In this last quest, they are looking at a close relative of the American Beech, the Japanese Beech (which naturally co-evolved with the nematode), to see how it reacts to the nematode. Vieira and his colleagues hypothesize that if they can understand key mechanisms involved in this process, they may gain insights into how natural resistance mechanism(s) can control the nematode population and prevent BLD.

Preliminary data has also shown some potential resistance among some American Beech trees, so learning more about how resistance works appears to be a promising approach. However, Vieira is quick to note that, “we need more people working on this complex biosystem. I think the basic research will help us in the breeding process to move faster.

“If you know the resistance mechanism(s), which genes are involved in resistance, then you can use that knowledge to identify potential resistance trees in the field using molecular markers and incorporate those trees in a breeding program to establish resistant germplasm.”

For now, Vieira recommends that people who see affected trees should contact their state’s forest service to help them track the disease. – By Kathryn Markham, ARS Office of Communications