Solving the Mysteries Behind the World’s Most Widespread Zoonotic Disease

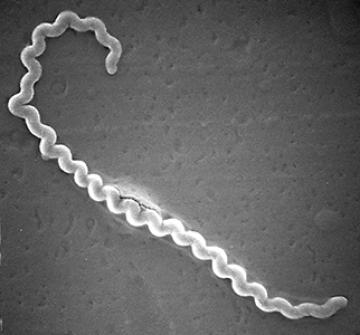

Scanning electron micrograph of a leptospire.

Leptospirosis is a serious zoonotic disease that affects both animals and humans. This bacterial disease is commonly spread through the urine of infected animals and rodents, including wildlife and livestock such as cattle and swine. Humans can contract leptospirosis by having contact with water (such as by swimming, rafting, or kayaking) or soil that has been contaminated by urine or body fluids of infected animals. Although this disease if often spread through urine, transmission can also occur in the genital tract of domestic animals.

Humans who contract leptospirosis may suffer from a range of symptoms, from a mild fever to massive pulmonary hemorrhage. For livestock, the disease can result in poor milk yield, reproductive failure, and in some cases, severe acute disease, especially for dairy and beef herds.

“Leptospirosis is caused by a very unusual and unique bacteria,” said Jarlath Nally, research microbiologist at the National Animal Disease Center (NADC) in Ames, IA. “Very few people work on it, the diagnostics are limited, and research is challenging because the bacteria that causes the disease are very difficult to grow in the lab.”

Leptospirosis is not a new disease; it was first described in 1886. Globally, the disease kills over 50,000 people a year and infects over one million. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention described it as the most widespread zoonotic disease geographically.

Human infections can be treated with antibiotics, but the condition is considered rare in humans and can be difficult to diagnose. Vaccines have been developed for livestock, including dairy and beef herds. However, the vaccine protects only against specific variants of Leptospira, the bacteria that causes leptospirosis, and protection dwindles after one year. There are more than 38 species and hundreds of serovars of pathogenic Leptospira.

“It gets complicated because there are so many variants of this disease” said Nally. “And the vaccines being used today are based on variants isolated over 30 years ago.”

Detection is also a problem. Infected animals often appear asymptomatic. Stakeholders may not be aware that their herd is infected until they notice an increase in abortions or reproductive failures. Further complicating matters are the diagnostic tests, which are not always accurate.

ARS researchers Ellie Putz and Luis Fernandes working to elucidate pathogenic mechanism of leptospirosis.

“We’ve done a lot of work to improve diagnostics,” said Nally, “but there are limitations, and stakeholders need to be aware of that.”

Nally and his research partners are looking to improve diagnostics, testing, and current vaccine strategies to provide cross protection against multiple variants of Leptospira. To date, they have generated a large repository of isolates of Leptospira from a range of domestic (cows, bulls, horses and dogs), wildlife (rats, mice, mongoose, red panda), and environmental sources (soil, water), including new species and serovars detected for the first time in the U.S. They also created a new growth media that allows researchers to isolate the Leptospira bacteria directly from infected animal tissue at 37 degrees Celsius. This is an improvement over the old methods where Leptospira were previously restricted to isolation at 28-30 degrees Celsius.

“That’s a temperature more in line with standard laboratory processes,” Nally said. “But more importantly, it’s an environmental condition that’s more similar to the host.”

Researchers have also been able to genetically manipulate the bacteria, allowing them for the first time to identify, target, and silence certain genes.

“Not only silence a single gene, but we can actually silence two genes at the same time,” said Nally. “We were able to apply our technology to silence two similar genes to actually identify a virulence factor, rendering the bacteria completely attenuated, which provides new avenues to generate vaccines and apply it to different variants.”

Next steps for Nally and his research team are to map complete genotypes, complete serotypes, and identify virulence factors that facilitate the disease process. At the same time, they want to identify which variants are circulating in domestic and wildlife animal populations in the U.S.

“We are also interested in understanding how the disease occurs,” he said. “We are looking to understand why these bacteria are colonizing in the genital tract and why they're associated with reproductive failure versus strains that are associated with more severe acute disease. To understand the ‘how’ will help us develop vaccines that will cross protect against all the variants that are out there.” By Todd Silver, ARS Office of Communications