A Strong Ally in Biocontrol is Dwindling

ARS researchers are sweep netting (sampling), for lady beetles in a restored prairie tract as part of a 14-year survey of lady beetles in South Dakota. (Photo by Eric Beckendorf, ARS)

Move over, Superman. The iconic ladybug, or lady beetle, is an environmental hero to agriculture. Lady beetles are one of the most effective, natural ways to control crop-damaging pests such as aphids. A single lady beetle can devour hundreds of aphids in its lifetime, thereby curbing the need for pesticides.

Unfortunately, some lady beetles native to the United States and Canada are dwindling in numbers, according to Louis Hesler, lead research entomologist at the North Central Agricultural Research Laboratory in Brookings, SD. This could have significant implications for crop growers.

"In the early 2000s, soybean aphids came into the United States and really took off," Hesler said. "One of the main predators of aphid pests are native lady beetles, so it was natural for me to be interested in them."

While native lady beetles curb the aphid infestations, species of non-native lady beetles have arrived to cut in on the action. These exotic lady beetles, such as the seven-spotted lady beetle and the harlequin lady beetle, have spread rapidly throughout North America, invading various habitats.

"These include crop fields of grain, soybean, and corn, where native lady beetles are now forced to coexist and compete with non-native species for prey," said Hesler. "Moreover, when native and non-native lady beetles encounter each other, the non-native species are much more likely to consume the native species."

While the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) lab in Brookings has documented declines in three kinds of native lady beetles since the 1970s, Hesler and his team have been researching native and non-native species as part of a follow-up study conducted from 2007 to 2020.

"Over the 14-year study in eastern South Dakota, we sampled 17,338 lady beetles comprising 10 species … seven of which were native and three were non-native," added Hesler.

The ARS team tracked lady beetle populations in six habitats: alfalfa, spring small grains, winter wheat, corn, soybean, and prairie by sampling with sweep nets or through visual searches. They discovered substantial reductions in lady beetle abundance.

Hesler’s team documented significant decreases in late-summer populations of native lady beetles in corn and soybean fields, specifically.

"This could lead to reduced overwintering populations of native lady beetles that typically emerge the following spring to colonize these crops," said Hesler, adding that the annual cycle of native lady beetles in both early- and late-season crops could be severely disrupted. Additionally, the Brookings team’s study showed relatively high abundance of both the seven-spotted and harlequin lady beetles, which is notable considering neither non-native species was known to occur in eastern South Dakota through prior ARS studies.

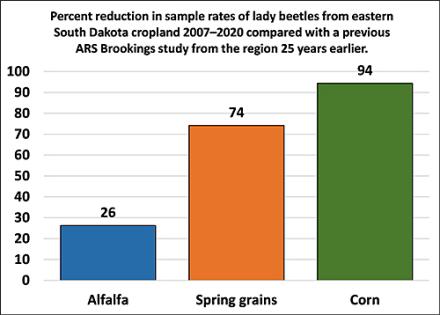

Furthermore, the study found a substantial decrease in overall lady beetle abundance in alfalfa, spring grains, and corn, compared with a previous ARS Brookings study from the region published 25 years earlier (see infographic at right).

ARS is continuing its research, conducting inventories of native and non-native lady beetles in additional states such as Maine, Hawaii, and South Carolina to help farmers manage pests to ensure crop productivity. — by Tami Terella-Faram, ARS Office of Communications

You May Also Like: