Taking the Bite Out of a Dangerous Cattle Foe

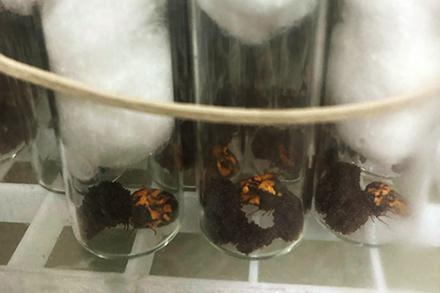

Ticks laying eggs in culture. (Photo courtesy of Lauren Maestas, ARS)

Cattle fever ticks are parasites that transmit a deadly disease that had been eradicated from the United States since the late 1940s. However, cattle fever ticks are still present in other parts of the world, and continually return to the border area of the U.S. from Mexico via deer, stray livestock, and from nilgai, an antelope species originally from India, which were brought to the United States as zoo animals in the 1920s and were later released in South Texas. If cattle fever ticks were to reestablish in the U.S., then it would affect cattle production, trade, and the health of our livestock. Cattle fever ticks can kill cattle by feeding on too much of their blood. Fever ticks can also transmit Babesia, the agent causing Babesiosis, a serious disease that can be fatal in cattle.

Cattle fever ticks greatly affect the meat industry by decreasing milk yields, increasing death and morbidity in the cattle, and by limiting export of cattle outside of the U.S. because other countries are cautious about the disease these ticks may carry. Keeping this tick eradicated contributes to the U.S. beef supply being high quality, plentiful, and inexpensive.

ARS researchers are studying a multitude of tools to help reduce the cattle fever tick population in the U.S. John Goolsby, an ARS research entomologist with the Cattle Fever Tick Research Unit in Edinburg, TX, has developed ways to treat the nilgai antelope with sprayers positioned into the landscape on ranches. As the nilgai go through the fence crossings, they are sprayed with entomopathogenic nematodes, which are soft bodied, non-segmented roundworms that are sometimes parasites of insects and other arthropods. The nematodes kill the tick. Because the nematode is native in the local environment, it’s a solution that works with nature itself to make the host animal more resilient to this exotic tick. Researchers are also working on a botanical pesticide that is made of different organic oils from flowers and various plant components, like citrus and cedarwood. One treatment being investigated is a botanical pesticide called “Stop The Bites®”, that is applied using an automated sprayer when the animals go into a pen to drink water.

“We're collecting the off-host larval ticks to see what kind of an impact the native nematodes are having on the cattle fever ticks to determine if that would be an adequate form of treatment in the field for this life stage,” explained Lauren Maestas, a research ecologist at the Cattle Fever Tick Research Unit.

Researchers are also trying to find the correct places in the animal’s environment to target for the treatment of this parasite and the disease it can carry. They first have to find out if the treatment procedure is going to work; then they can determine how to implement the treatment for wildlife that are in constant movement and are not accessible to easily get the treatment. For example, researchers are using radio collars to locate the different routes the animals utilize their patterns to determine where to better place the treatments.

“Part of the USDA’s mission is to reduce the use of pesticides and acaricides (pesticides used to kill ticks),” said Donald Thomas, a research entomologist at the Cattle Fever Tick Research Unit. “So, we are moving into a new paradigm to utilize vaccines in order to control the ticks.”

Researchers in Texas are looking to find a vaccine with a higher level of effectiveness than BM86, a current vaccine that is between 55% to 71% effective. Charluz Arocho, a research specialist and graduate student at Texas A&M University, has been working on a new vaccine using extracellular vesicles (known to facilitate intercellular communication in diverse cellular processes such as immune responses and coagulation), specifically exosomes and microvesicles (which are 2 of the 3 main subtypes of extracellular vesicles) because they are more effective as vaccine candidates.

This team of researchers aim to find a vaccine that is more effective and can eradicate the tick, helping farmers provide a higher-quality product and keeping the meat industry thriving in the United States. By Olga Vicente, ARS’s Office of Communications.

Also in our series on cattle: