What’s the Answer to AMR?

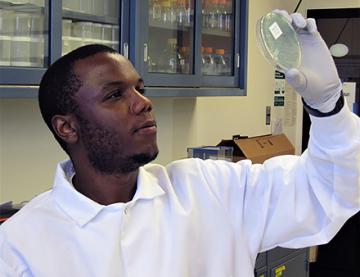

Adelumola Oladeinde examines E. coli isolates recovered from broiler chickens. (Photo courtesy of Adelumola Oladeinde)

ARS researchers study whether the path to reducing antimicrobial resistance is right underfoot.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of biggest health threats to humans and animals worldwide. In 2019 alone, nearly 5 million people died from drug-resistant bacterial infections. Scientists from the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) have joined a multinational holistic approach called “One Health” to combat the scourge of AMR.

“Increasing concerns over AMR have led the world’s poultry production systems to significantly reduce antibiotic use and to raise birds under ‘no antibiotics ever’ programs,” said Kim Cook, ARS national program leader for food safety in Beltsville, MD. “In fact, most of broiler chickens produced in United States are raised that way.”

However, despite the best efforts of the industry, antimicrobial resistant bacteria are still being detected.

With few options to curtail the spread of pathogens, farmers have been left in unexplored territory. To help, ARS deployed a team led by Ade Oladeinde, a microbiologist with the U.S. National Poultry Research Center in Athens, GA, to blaze a trail.

“We have to understand the reservoir and types of AMR common to poultry environments before we can reduce the spread and reduce the risk,” Oladeinde said.

The “One Health” concept recognizes that the health of humans, animals, and the environment are strongly connected and that reducing the development of AMR bacteria requires a multifaceted approach.

Oladeinde explained that AMR occurs when a microbe can survive or withstand treatment from antibiotics or antimicrobials it was initially sensitive to.

A major bottleneck to AMR research was the lack of accurate research tools. Oladeinde and his team undertook that challenge.

Adelumola Oladeinde evaluates fresh and reused litter collected from broiler house. (Photo courtesy of Adelumola Oladeinde)

The team developed a high throughput tool to identify all AMR genes commonly associated with poultry production, a bioinformatic tool to analyze bacterial genome sequences, and improved a DNA sequencing tool to identify the bacterial species that spread AMR within the chicken microbiome (all the bacteria in the chicken). They also developed broiler litter microcosms (mini environments) to simulate a chicken house.

The investment in litter development quickly paid dividends. Chicks infected with Salmonella Heidelberg were raised on fresh pine shavings or reused litter (a complex environment made up of decomposing pine shavings, feces, uric acid, feathers, and feed) for 14 days. An examination of intestinal contents showed a dramatic difference.

“Over 37.5% of the samples from chicks on fresh litter acquired resistance to three antibiotics: gentamicin, tetracycline, and streptomycin,” Oladeinde said. “Contrastingly, no chicks raised on reused litter had acquired those resistances.”

Oladeinde found antibiotic resistance genes on plasmids, genetic structures that can replicate independently of the chromosomes. He also found that the microbiome (all the bacteria) of chickens raised on fresh pine shavings differed significantly from the microbiome of chickens raised on reused litter.

Together, the results suggest that bacterial populations from reused litter could provide resistance against the transfer of multidrug-resistant plasmids to Salmonella.

“Chicks on reused litter performed better than those on fresh litter. Clearly, this indicates that the bedding material/litter plays a critical role in controlling the level of AMR pathogens. However,” he cautioned, “one needs to be careful about generalizing our results.”

Oladeinde’s reused litter had been used previously to raise three flocks of broilers; it’s common for litter to be used for six flocks. He said they were not sure if there was a “magic” number to the litter’s age, so there is a clear need for study.

“I believe our results contradict public opinion about reused litter. The general notion is that reusing litter must be bad for public health,” he said. “On the contrary, our results clearly show that it is more beneficial to the chickens and food safety to reuse litter. I think that’s cool because it reveals the power of a good, resilient microbiome.” – By Scott Elliott, ARS Office of Communications.

You May Also Like