Working Across Borders to Fight ‘Mite’-y Big Problems

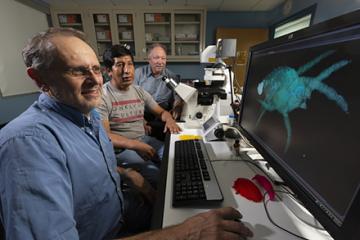

At the ARS Electron and Confocal Microscopy Unit in Beltsville, MD (left to right), Ron Ochoa, an ARS entomologist and mite expert; Javier H. Maldonado, a visiting entomologist from Peru; and Gary Bauchan, lab director, use a laser scanning confocal microscope to identify plant-feeding mites found on a recent trip to the highlands of Peru. (Stephen Ausmus, D4245-1)

It’s hard to fight back when you don’t know what the enemy is, especially if they’re nearly impossible to see and they number in the millions.

There are more mite species in the world than all other types of arthropods put together, perhaps up to 11 million, said Ron Ochoa, mite expert and research entomologist with USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Beltsville, Maryland. Ochoa bases his claim on the observation that almost every insect has mites on it, and there are many other mites that feed on every plant and animal.

Most mites are microscopic in size, but through sheer numbers their feeding habits can spell big trouble for the world’s economy, climate, and ecosystems. That’s where the ARS Electron and Confocal Microscopy Unit (ECMU) comes into play – by helping scientists from around the world see the results of their work or, sometimes, get a first glimpse of the focus of their attention said Gary Bauchan, ECMU director.

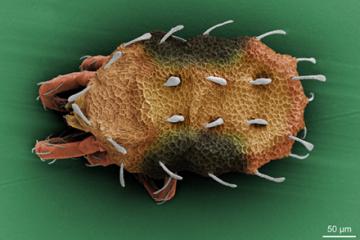

A colorized scanning electron microscope image of a new, unknown spider mite causing damage on small native bushes in the highlands of Peru. (Electron and Confocal Microscopy Unit, D4259-1)

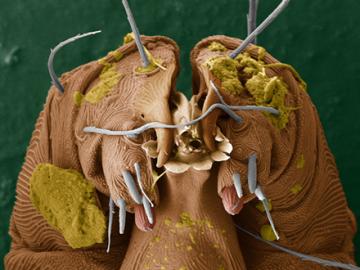

The ECMU has several high-tech tools at its disposal, including a scanning electron microscope that can provide magnification up to 100,000x. This ultra-close scrutiny of insects that measure only about 100 microns in size (one 1,000th of a millimeter) helps scientists like entomologist Javier Huanca Maldonado identify problem pests and come up with a way to control them. Huanca is visiting ARS from Peru’s Universidad Nacional de San Agustin de Arequipa.

“You can spend a lot of money on the wrong control measure if you don’t know the exact species,” Huanca said. “What might be a natural enemy of one mite may not be for a different species.”

Huanca is working with Ochoa and the ECMU to identify and describe species of mites in the peatlands and highlands of Peru, as well as the agricultural fields of Arequipa province. In the peatlands, an area known for its capacity to store carbon, an undescribed species of spider mite is covering plants with webbing that interferes with photosynthesis (how green plants use sunlight to synthesize foods from carbon dioxide and water). Starved of food, the plants die and cause breakdown in the soil nutrient chain.

In Peru, ARS entomologist Ron Ochoa (left) stands with collaborating entomologists Javier H. Maldonado and Alexander R. Rodriguez at the entrance to the experimental research station where they looked for plant-damaging mites. (Ron Ochoa, D4241-1)

“It’s amazing that you find, at an elevation of 12,000, feet a little mite chewing up and completely disrupting an entire ecosystem,” Ochoa said. “We must identify this mite and find its natural enemies because it is affecting all of the highlands.” Huanca, Ochoa, and Bauchan use the ECMU’s low-temperature scanning electron microscope to obtain high resolution images of the mites they’re interested in. They then compare those images to known species of mites to obtain a precise identification, study its behavior, and, potentially, determine a method for controlling them.

Agricultural plants and animals have their issues with mites, too, and when they wind up on the mites’ menu, problems may turn economic.

Proper identification of arthropods is key to the import/export business; if a nation discovers an unidentified mite in a shipment, it may ban the import at the cost of millions or billions of dollars. If, however, an inspector from U.S. Customs and Boarder Protection or USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) finds a mite and discovers that it already exists in this country, then the shipment may be allowed because there’s no new threat. Ochoa and the ECMU are frequently called upon to identify mites, and then it’s up to the APHIS to determine if the shipment will be allowed into the country.

A low-temperature scanning electron microscope image of the face of a Mononychellus species of mite found in highland trees in Peru. (Electron and Confocal Microscopy Unit, D4260-1)

“Dr. Ochoa spends about half his time conducting mite research and the other half working with APHIS trying to identify mites that have been discovered in shipments – and he has only three or four hours to make the identification,” Bauchan said.

“Just this morning, we got an email from Guatemala telling us that their corn was being attacked by a red spider mite and asking for our help,” Ochoa said. “Here we are, Javier and I, working on a closely related mite from Peru. We’re thinking, ‘There’s one culprit,’ but we’re trying to get more information.”

“It is necessary that we interact with scientists from other countries so that we understand what insects and mites they have and they understand what we have,” Bauchan said. “Together we can build a community and learn from each other. We don’t know what we don’t know until we can look at it and identify it.” – By Scott Elliott, ARS Office of Communications.